Chapter 6 - Down the Mexican Baja Coronados IslandsOn Monday morning, December 4, we topped off the diesel tank and headed south. Since we didn't get away until after lunch, we planned to anchor for the night at the Coronados Islands, then make the 45 mile trip to Ensenada the next day to clear customs. Although the prevailing winds are from the north, that day we had them from the southeast . . . right on the nose. One starboard tack down to Tijuana, then a port tack out to the Coronados Islands and we expected to arrive just before sunset.The weather had different ideas. Despite clear skies everywhere else, the islands were socked in with thick fog. That cut out the sun's light an hour early and we were left in the dark and the fog. We dropped the sails and motored toward the islands, navigating 100% with radar. We threaded Baba BarAnn between the middle and the south islands, then maneuvered into a small cove, and dropped the anchor when we hit the 5 fathom mark. This was all done without ever seeing land! The radar showed we were in a cove with about 50 yards on three sides, and open to the south. When we turned off the engine, we could hear breakers all around us. We were anything but comfortable. Knowing that sleep would be impossible in such a tenuous anchorage, we decided to continue south. So up came the anchor, and we threaded our way back out, between the Islas Los Coronados. I'll never do anything as stupid as that again. We then hoisted the sails and started to beat our way south in dense fog. About every hour or so we'd tack, not playing the wind shifts. We didn't want to arrive at Ensenada before sunrise. That was a mistake, and we ended up sailing all night long, getting only 20 miles further south. In essence we ended up sailing back and forth, east and west. Then the wind died completely, so we had to motor the rest of the way to Ensenada, in order to arrive there before dark!

EnsenadaEnsenada is the largest town in the Baja, with about 250,000 people. The air and water pollution was terrible. An enterprising young guy motored out in his panga (18 foot open boat) and tried to get us to use his mooring at $5 per night, with "taxi" service at $1 per person per trip. No thanks. We anchored a little further away from town, next to two other cruisers. The boat next to us recognize us from Mission Bay, and even remembered my name. We rowed over, enjoyed a cerveza, and found out the routine for completing all the paperwork. The next morning, we motored the dinghy into town and completed all the red tape in just over an hour. It really wasn't too bad. Then we headed for the fish market. We were the only gringos, and we slowly checked out all the stalls. A small, but muscular boy, perhaps 14 years old, knew a little more English than the others, and had a nice style, as well as some nice looking fish. We picked up a fresh looking fish and said "How much?" "Five dollars!" That seemed high, so Candace asked how much it weighed. He threw it up on some scales above his head, and it read 1.2 kilos. I'm not sure whether or not his hand was on the scale, but that wasn't important. This fish certainly wasn't going to be sold by the pound. Candace said "5,000 pesos," he said "10,000." After a few more rounds of negotiations, we settled on 7,000, or about $2.65. Welcome to Mexico. Actually bartering was kind of fun. We both thought it was a fair price. Then the boy expertly filleted our fish and we were off. We stopped at a Fish Taco stand (they have lots of them), only to buy some fresh cilantro to season our fish. The entire transaction took place in Spanish as Candace asked "Puedo comprar cilantro?" (Can I buy cilantro?) We gave the girl 15 cents for a large bunch and then we went back to the boat. We had to get out of the choking air and smelly harbor as soon as possible. After lunch we headed to Islas Todos Santos, just 10 miles east of Ensenada.

Islas Todos Santos

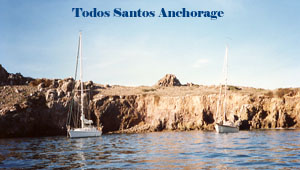

Just a few hundred yards off the island our depth sounder still wasn't registering. Since it's good for depths down to 650 feet, I was sure that all the oil in Ensenada had fouled the transducer. But shortly before reaching the island, it started registering 500-600 foot depths. The one good anchorage is a cove about 250 feet in diameter, [good picture of the cove] with rocks all around on three sides, and there was one boat in there already. As we entered, its skipper waved, so I knew he wasn't going to be too grumpy about sharing his secluded cove with us. He said he had a stern anchor out, and suggested we tie a stern line to shore. In tight quarters between his boat and the rocks, I spun Baba BarAnn around, and headed back out so Candace could drop the bow anchor and 200 feet of chain. After backing down and setting the anchor, I grabbed a bag in the lazarette that contains the stern anchor rode, jumped into the dinghy, tied one end of the rode to the boat, and then rowed to shore to find a spot to tie our line. Finding nothing but steep, sharp rocks, it didn't look good when I scrambled to shore with the dinghy painter and the last 10 feet of anchor line. Just around the corner of the rock I'd landed on, I found a large metal ring sticking out. Just what I needed. Charlie's Charts of Mexico had mentioned such a ring, but I didn't think I'd be lucky enough to land my dinghy on just the right rock. I quickly tied a bowline, and got back to the boat as fast as possible. Meanwhile Candace had her hands full keeping the boat off the rocks. Once on board, I quickly winched in the stern line while Candace brought in 50 feet of anchor chain, thereby pulling us away from the rocks, in between the anchor and shore. I'd noticed that our neighbor's boat, Moko Jumbi, was a Hylas 42 with a Seattle home port. After quickly consulting the computer, I jumped back on deck and said "Thanks for the help Jim! You're Jim O'Connell aren't you?" We hadn't met before so he was really confused. I'd been told by the head of the Seattle Crow's Nest marine store, last July, that I should look up his friend on a Hylas 42 who had similar cruising plans. The computer didn't have his boat's name, but it had enough information for an educated guess.

We dinghied over and became more acquainted. I told him how I'd known his step-father, Duff Kennedy, who is the head of one of Seattle's largest pension asset management firms. He wanted to know what other information we had in the computer! He and his friend, Robin, both commented on our expert anchoring routine. I wanted to agree that a lot of things were done right, and some a little bit lucky (like finding that ring in the rock, and having just enough line), but just bit my tongue. During our trip around Vancouver Island last year we had much practice with stern lines, and we'd done a lot of anchoring. That night's dinner of fish poached with tomatoes, onions, green olives, and fresh cilantro was great. Our first day in Mexico was a big success. I just hope it's a harbinger of many good times to come. The next morning I picked up Jim and Robin and we dinghied to shore to take pictures and climb around. Then we weighed anchor and headed south.

Five Days OffshoreAfter three glorious hours of sunshine and favorable winds, the winds died and we were becalmed. We're really trying to preserve our diesel, and couldn't motor at the drop of the wind. This looked like a good time for a "doldrums drill." So we waited, and waited, and waited for the wind to come up. After TWELVE HOURS we were still in the same place, it was 2 AM, and we had enough. On went the motor for about nine hours. Shortly before noon some favorable winds picked up from the Northwest, and we were off. Smooth seas, and fair winds from the northwest. Perfect. We headed out, as much as 100 miles offshore, and charged down the Baja coast. We sailed non-stop for five days, generally with brisk Santana winds. At times there were gusts over 30 MPH, but generally we had 15-25 knot winds. We were moving. The first few days were tough, only because we couldn't get used to sleeping with the noise and motion of the boat. Exhaustion is a good remedy for that problem, so after three days with virtually no sleep, I finally got the hang of it. There's a natural tendency for your body to resist the rolling motion. When the boat rocks one way, your muscles react the other way. How many times have I heard, you've got to go with the flow. Not only was I exhausted, but my thigh and shoulder muscles were sore from resisting. Offshore passages are not easy. When you're not on watch, you lie down with eyes closed, hoping to sleep 10 minutes here or there. There are four different sleeping areas on Baba BarAnn. The vee berth where we normally sleep at the bow of the boat, is too noisy and has too much motion when we're sailing. Another alternative is the aft cabin for port or starboard tacks. The main salon has one settee on the starboard, and one on the port. They're probably the best, especially when it's very rocky. However, the person on watch uses the starboard area in front of the nav station, and could disturb someone trying to use the port settee. Being "on watch" entails carefully looking around the horizon every 20 minutes and sometimes checking the radar screen. You can set a timer to wake yourself every 20 minutes if there are no problems with steering, although it's better to stay awake. When motoring, it's quite easy, since the auto pilot steers flawlessly, and there's no need to conserve electricity. That means the radar can be on all the time. Under sail, the wind vane generally has no problem steering, especially if the winds are fairly consistent. Light winds, with a quartering sea, on a broad reach can be a problem, since a wave can force a gibe. The "on watch" person is fully responsible for keeping the boat sailing safely and in the desired direction. Sail reefing or changing is a two person job, so the "off watch" must be awakened. A thermos of hot water is ready for coffee or tea, while candy bars, fruit, nuts, and other munchies are handy. About every hour or so a dot is put on the chart to plot our dead reckoning, along with the time, log (odometer miles), and course steered. I usually read during night watches, while Candace fights seasickness and sleepiness. Sometimes we listen to tapes on the "walkman."

Celestial NavigationOf course we saw no land, and only a very few boats would show up on the horizon or radar. We were too far south so the LORAN was unreliable. We didn't have SatNav or GPS. That meant I could now practice celestial navigation when it really counted. Our starting position was plotted on the chart from our last land observation. To this we added our "dead reckoning," (DR,) plots. A "running fix" was obtained using the sextant and a hand calculator. It would provide two crossing lines of position (LOPs) from sun sights, so we marked that spot on the chart and compared it with our assumed position from DR. Hopefully the two were close. Based on wild guesses about the current, the perceived quality of the sun sights, and divine intervention, I then determined a new starting point, from which we recommenced DR plotting. The next day another running fix showed us to be about 20 miles behind our DR position. Either my celestial was off, or the log on the boat was off. Since celestial showed that we went 120 miles in the last 21 hours, not 140, I recalibrated (recalibrated seems a bit too refined a term for the action . . . how about re-eyeballed) the log to give 15 percent lower readings. Forget that this was only the first day I had used celestial navigation . . . of course it was more accurate than the expensive "odometer" on the boat. This celestial stuff is supposed to be really accurate, although it was a bit tricky getting readings with my sextant when the boat was rocking in 5-8 foot waves. Anyway, that's what I did. That night I got a fix using two stars. Star fixes at night were possible because the full moon made the horizon visible. The next day our DR position was within two miles of a celestial position obtained with three stars. About twice a day we would have radio contact on the 40 meter band with Chuck on Carina. He'd left two days before we had, but our non-stop trip had caught up with him. He was traveling south, along the coast, while we headed ESE . . . both converging on Bahia Santa Maria with an ETA of noon on December 13. At sunrise I spotted land . . . just a mountain. Was it perhaps Mt. San Lazaro, on the north entrance to Bahia Santa Maria. That mountain should have a bearing of 77 degrees magnetic, not 66 degrees. I'm either further south, or somehow that's a very high mountain further north and inland (off my charts) from Mt. San Lazaro. Of course I'm fully aware that it could be one of a dozen mountains on the coast. Where am I? It's starting to get tense. My confidence and celestial bravado are starting to shake. Candace suggests calling Chuck, who has satellite navigation, to get a visual check on our landfall. I didn't want to resort to that unless it was absolutely necessary. I'd gotten us this far (wherever "this" was) so we're not going to cheat just 20 miles from the finish. Candace has a good suggestion of quickly taking another sun sight, and it places us about 5 miles further south from our DR track. Now I'm comfortable that the mountain is Mt. San Lazaro. We did it! We found that needle in a hay stack on the Baja coast, using celestial navigation! We turn slightly to the north and confidently head toward the bay.

Bahia Santa MariaA little later, I call Chuck to ask if that's him I can see, sailing by the Cabo San Lazaro lighthouse. Yup, and he sees Baba BarAnn coming in from the SW. I challenge with "First fish wins a beer!" We meet up at the entrance to the bay, just 15 minutes after he'd arrived. Of course I was trolling a lure. I started to pretend like I had a big fish on . . . but it was too late. I saw him dip his net into the water and lift a small fish. "Chuck, you're not going to count a fish under 12 inches, are you?" It's hot and sunny. That night we have dinner on Carina, enjoying some of the tuna fish that Chuck caught a few days ago. They're not as thrilled since they've been eating tuna fish for 3 days! I have a slight case of "immotion sickness" since it's so calm in the bay, but I'm extremely happy with the successful completion of our first long passage as a couple. Excluding the half day bobbing up and down during the "doldrums drill," we traveled 621 nautical miles in 4.5 days, at an average speed of 5.75 knots . . . 138 miles per day. About 20% of the time we were motoring at the same 5.75 knots. Seasickness was not a problem, although we took some pills the first few days. I also found out that there is a strong southerly current which explains why I ended up 5 miles south of my assumed position.

December 14 I traded a small bottle of Canadian Club and a third of a loaf of bread that Candace baked yesterday for four lobster . . . it worked out to about 75 cents per lobster. They're spiny lobster, about one pound a piece. Candace caught 4 Pacific Herring by jigging for them with little hooks just off the stern. They're a pretty fish, about 10-12 inches long, with yellow around the "ears." Chuck and Bev traded for their lobsters and came over to Baba BarAnn for dinner. We had pan fried fish, two lobsters per person, potato salad, veggies, and cold sauvignon blanc. Somehow we even found room for chocolate cake and coffee. The solar panels could easily supply enough electricity for the water maker, and have some left over for the refrigerator. So this is Baja life. Nice. Final Leg South to Cabo San LucasJust 160 miles south to Cabo. We left at 7 AM, hoping to arrive during daylight the next day. It was drizzling . . . just like Seattle. Soon the sails were up and we were beating south. Yes, the wind was directly from the southeast where we were heading. As the wind picked up, we reefed the main. Later we took down the staysail. When the wind built to 25 knots, and the waves increased, we had to fall off a bit. Once again back and forth, east and west, making very little progress toward our destination. When the wind rose to 30 knots, we stopped beating (the boat as well as our heads against the wall) and started motoring south. All night and day we pound against the waves. That night rain squalls were interspersed with lightning, wind, and waves. Eating and sleeping was impossible. Maintaining balance and our stomach was a full time occupation. This passage ranked down there with Cape Mendocino for terrible trips. Late the next morning, the sun came out for a brief instant, allowing us to use the sextant and "shoot the sun." In order to get our exact position, we combined an east-west celestial line-of-position with our radar's north-south line six miles offshore. Three more hours to go. What a miserable passage. At times the motor could only make one knot forward progress against the wind and large waves. Crashing off the top of one particularly large wave, the doors to the chain locker came open, spilling wet chain over our bedding. Because we don't sleep in the vee berth during such violent motion, we didn't notice our soggy sheets until arriving in port. Finally we turned the corner into Cabo San Lucas. (Picture of Cabo before all the development) The sun was now blazing hot and the weather was glorious. We squeezed into the crowded inner harbor and dropped the anchor. This was 1989, well before CSL was developed with hotels. Four more times we re-anchored that night, trying to fit. Bedding and clothes were brought on deck to dry out. After dinner we were invited to Bequia Chief for tea and cake. We first met this boat in San Luis Obisbo, then later Santa Barbara, more than two months ago. Actually, we had met their son, Tavis, who's an extremely affable, outgoing 14 year old. He let me copy one of his computer space games. Finally we meet Tavis' parents, Tom and Jan, and little sister Jo. Like all cruising children, they're taking correspondence classes. Most American kids are taking a high school course produced by the University of Nebraska, or a grade school course produced by the Calvert School in Maryland. The Canadian children seem to be taking courses offered by the government. The next day we played the Mexican paper shuffle game. Clovelly, a Vancouver boat we first met in the Delta, said the record was one and a half hours for the process. So we walked one mile to the Port Captaina's office. Unlike at Ensenada, he said go to "inmigracion" first. Next we walked to the copy store, got three more copies that they needed in Ensenada (48 cents), then walked two miles to a 15' by 15' shack to get them stamped by "inmigracion." Then back to the Port Captain for more stamping. Finally, next door to the Taxman to get another form filled out and pay 5,780 pesos ($2.25). Because we walked pass the "inmigracion" shack several times before having the nerve to enter the barbwire yard, it took us two and one half hours. Next we "checked in" at Papi's Deli, the cruisers' main rendezvous point in Cabo San Lucas. We were boat number 133 this year. By the time the season's over, 350 boats will check in. Papi's runs the cruisers' VHF net where info is swapped, equipment is bought and sold by cruisers, and activities are announced. That night there was a free Christmas party put on by the downtown merchants. After lunch, we checked out some stores for some minor shopping (a.k.a. tried out our Spanish). Our language skills are substandard but acceptable in a pinch. Some things cost less, some more, but most are about the same as USA prices. We met Chuck and Bev who had just arrived almost 20 hours after us. They had some engine problems and motored very little. We both commiserated on the rough passage. We decided to avail ourselves of a real luxury. Miguel on VHF channel 14 picks up laundry at our boat, and then returns it all clean and folded for 12,000 pesos ($4.50) per six pound load. We stuffed three weeks' worth into a large sail bag and hoped it weighed less than 24 pounds.

|